Thyroid Function Testing: Advanced Interpretation and Clinical Significance

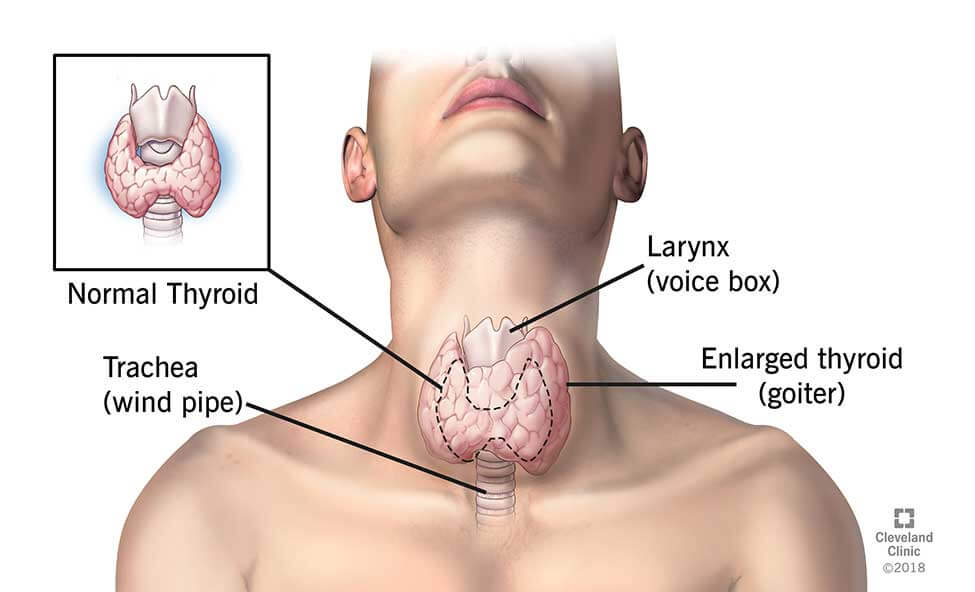

The thyroid gland, a vital endocrine organ located in the anterior neck, plays a crucial role in maintaining metabolic stability, thermoregulation, and overall hormonal balance. Aberrations in thyroid function can precipitate a spectrum of pathophysiological conditions, ranging from overt hypothyroidism to hyperthyroidism, each with significant systemic implications. The utilization of thyroid function tests (TFTs) constitutes the cornerstone of diagnostic endocrinology, facilitating nuanced assessments of thyroid physiology and guiding therapeutic interventions. A sophisticated comprehension of these biomarkers is essential for clinicians and researchers aiming to optimize patient outcomes and advance the understanding of thyroid pathophysiology.

Comprehensive Overview of Thyroid Function Biomarkers

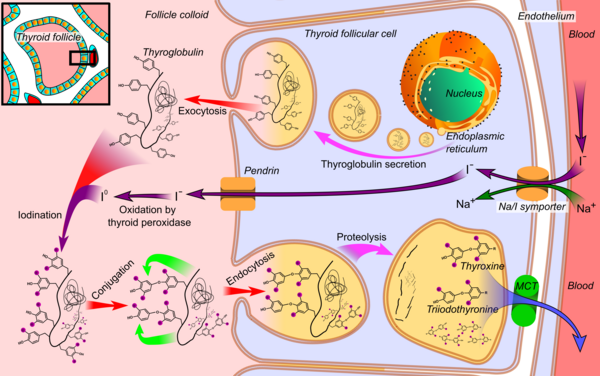

Thyroid function evaluation incorporates a panel of biochemical assays, selected based on clinical presentation, symptomatology, and differential diagnoses. These tests provide crucial insights into thyroid hormone synthesis, conversion, and regulatory feedback mechanisms, enabling targeted diagnostic and therapeutic decisions. These assays are indispensable in elucidating thyroid hormone synthesis, conversion, and regulatory feedback mechanisms.

Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH)

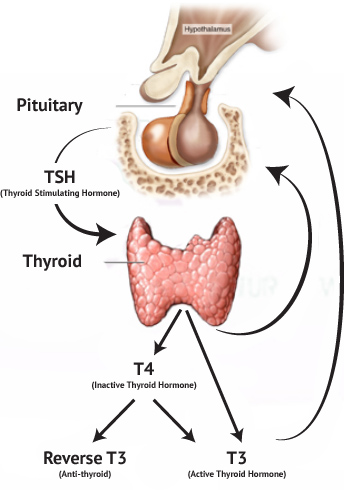

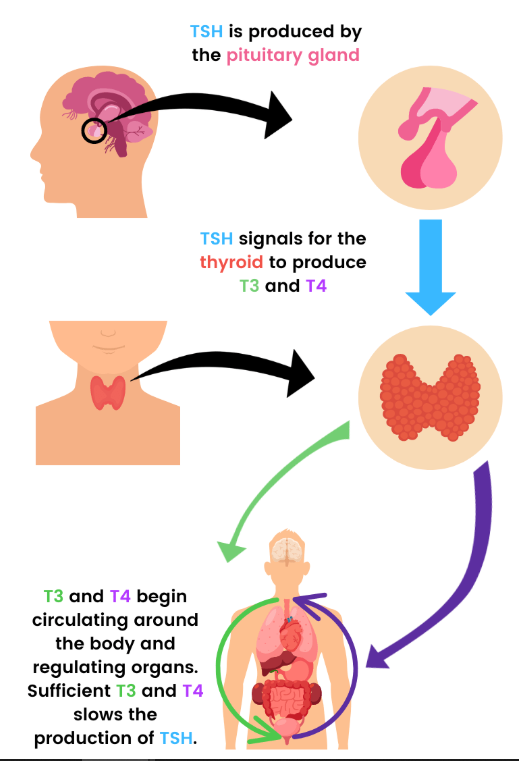

- Synthesized by the anterior pituitary, TSH exerts regulatory control over thyroid hormone synthesis and release via a negative feedback loop.

- Reference range: Typically 0.4-4.0 mIU/L, subject to inter-laboratory variability and population-specific considerations.

- Elevated TSH: Indicative of primary hypothyroidism, denoting diminished thyroid hormone synthesis and subsequent compensatory pituitary stimulation.

- Suppressed TSH: Suggestive of primary hyperthyroidism, often due to autonomous thyroid hormone overproduction or exogenous administration.

Free Thyroxine (Free T4)

- A principal secretory product of the thyroid gland, thyroxine (T4) undergoes peripheral conversion to its active metabolite, triiodothyronine (T3).

- Reference range: Approximately 0.8-1.8 ng/dL.

- Reduced Free T4: Corroborates hypothyroidism, particularly in conjunction with elevated TSH.

- Elevated Free T4: Characteristic of hyperthyroid states, often due to Graves’ disease or exogenous thyroxine administration.

Free Triiodothyronine (Free T3)

- T3, the biologically active thyroid hormone, modulates metabolic, cardiovascular, and thermogenic functions.

- Reference range: Typically 2.3-4.2 pg/mL.

- Elevated Free T3: Frequently observed in thyrotoxic conditions, notably in T3-predominant hyperthyroidism, which may indicate autonomous nodular thyroid disease.

- Decreased Free T3: Associated with hypothyroidism or non-thyroidal illness syndrome (NTIS), wherein peripheral deiodination is impaired due to systemic illness.

Thyroid Autoantibodies

- Autoimmune thyroid disorders are diagnosed through serological detection of specific antibodies:

- Thyroid Peroxidase Antibody (TPOAb): Elevated titers are pathognomonic of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and often present in Graves’ disease.

- Thyroglobulin Antibody (TgAb): Frequently observed in autoimmune thyroiditis and may have implications for thyroid cancer monitoring.

Reverse T3 (rT3)

- An inactive metabolite of T4, rT3 levels may be elevated in euthyroid sick syndrome, reflecting altered peripheral thyroid hormone metabolism due to acute or chronic illness.

Thyroglobulin (Tg)

- Primarily utilized in the follow-up of differentiated thyroid cancer post-thyroidectomy, thyroglobulin serves as a tumor marker and is often measured alongside anti-thyroglobulin antibodies.

- Primarily utilized in the follow-up of differentiated thyroid cancer post-thyroidectomy, thyroglobulin serves as a tumor marker and is often measured alongside anti-thyroglobulin antibodies.

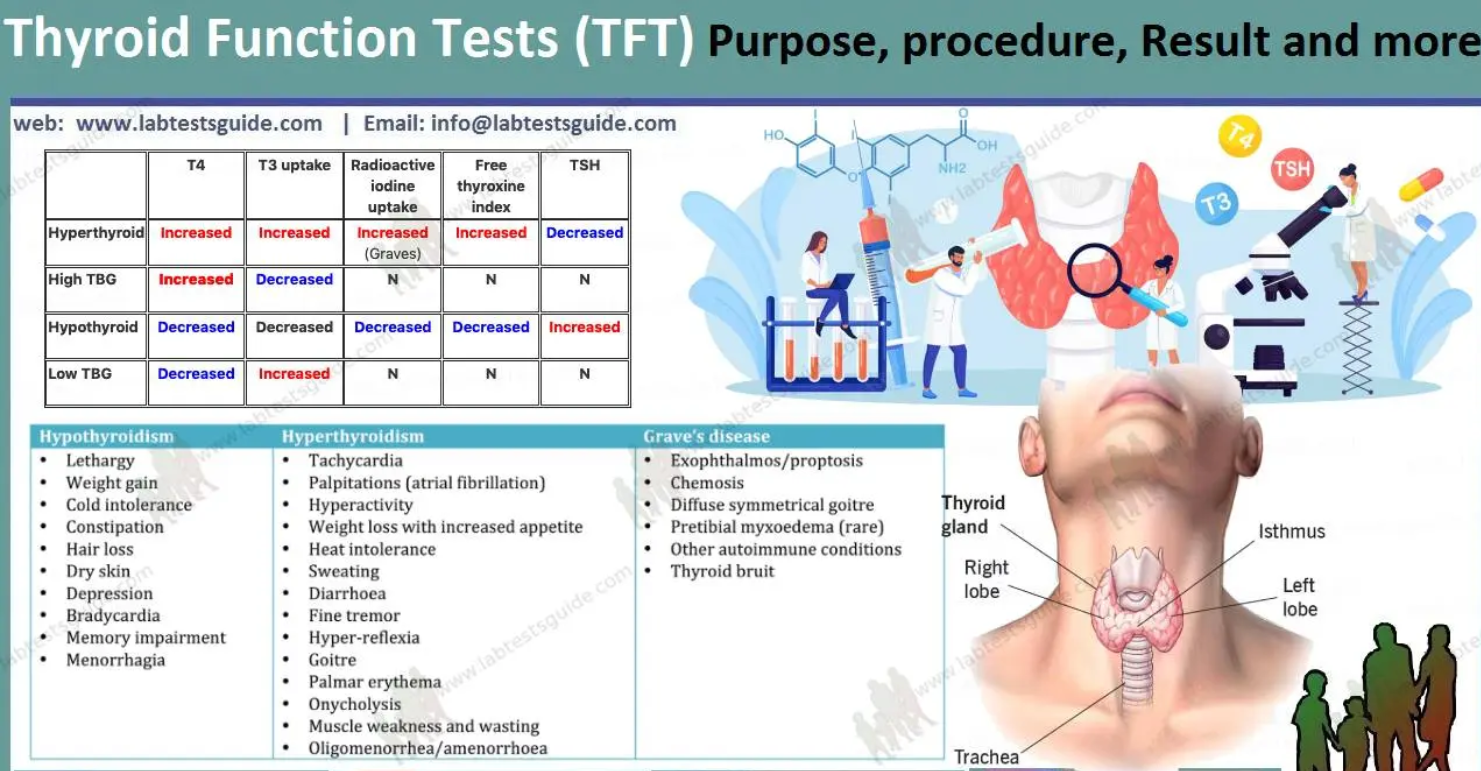

Diagnostic Interpretation of Thyroid Function Panels

An integrative approach to thyroid function testing requires a comprehensive analysis of biochemical markers to accurately classify thyroid dysfunction states. The interplay between TSH, free T4, and free T3 levels determines the nature and etiology of thyroid disorders.

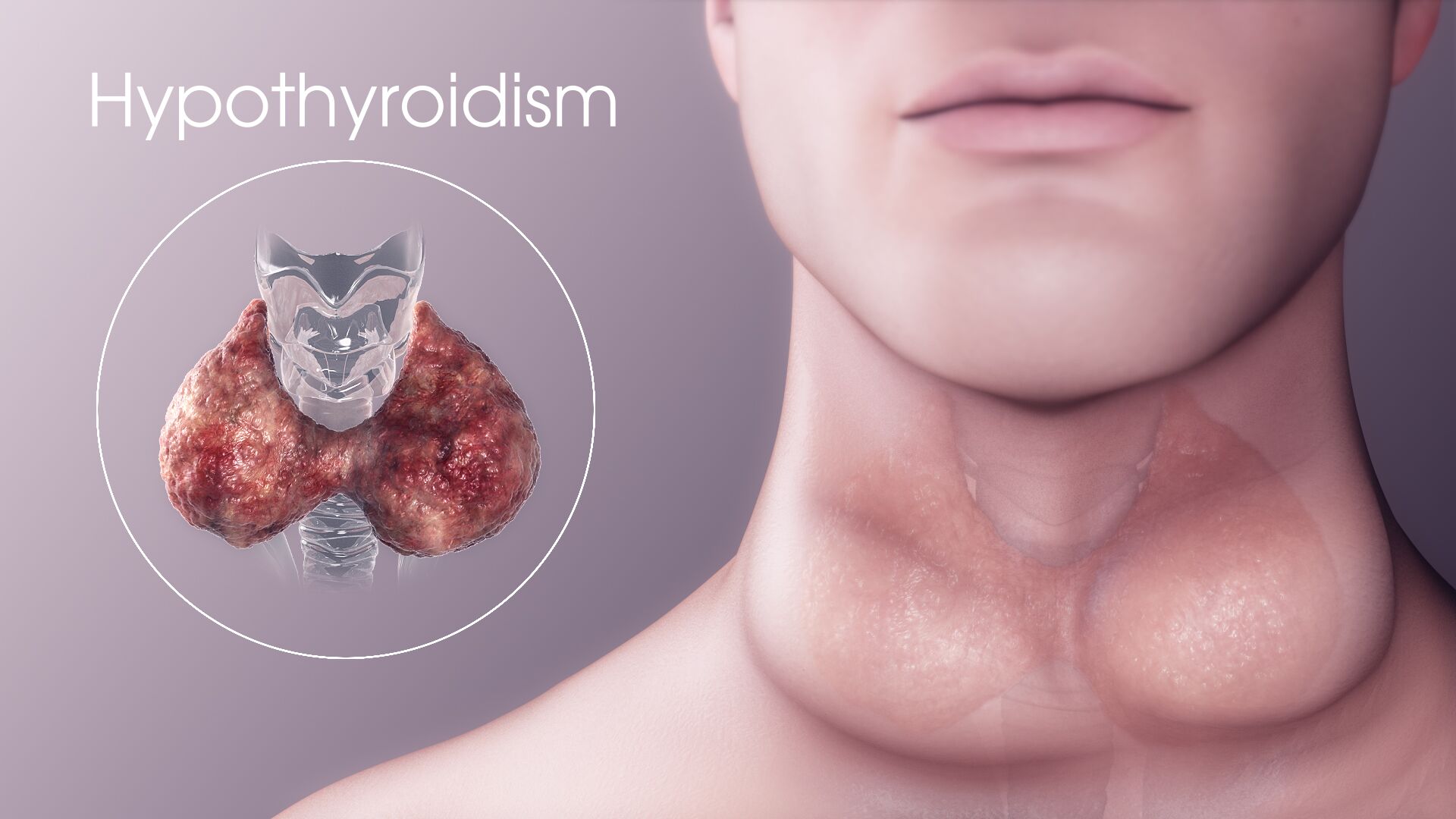

Primary Hypothyroidism:

- Elevated TSH

- Decreased Free T4

- Low/Normal Free T3

Subclinical Hypothyroidism:

- Mildly elevated TSH

- Normal Free T4

- Potential progression to overt hypothyroidism over time

Primary Hyperthyroidism:

- Suppressed TSH

- Elevated Free T4 and/or Free T3

Subclinical Hyperthyroidism:

- Low TSH

- Normal Free T4 and Free T3

- May predispose to atrial fibrillation and osteoporosis

Central Hypothyroidism (Hypothalamic/Pituitary Dysfunction):

- Inappropriately low/normal TSH

- Decreased Free T4

- Often associated with pituitary adenomas or hypothalamic disorders

Exogenous and Physiological Modulators of Thyroid Function

- Gestational Thyroid Adaptations: Pregnancy induces physiological alterations in thyroid hormone dynamics, necessitating trimester-specific reference intervals. Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) can transiently suppress TSH during the first trimester.

- Pharmacological Interactions: Agents such as amiodarone, lithium, corticosteroids, and biotin supplements can significantly alter thyroid hormone levels, necessitating careful interpretation of TFTs.

- Micronutrient Deficiencies: Iodine, selenium, and iron are critical cofactors in thyroid hormone synthesis and metabolism. Deficiencies can exacerbate thyroid dysfunction, particularly in iodine-deficient regions.

- Non-Thyroidal Illness Syndrome (NTIS): Acute and chronic systemic illnesses may alter thyroid function test profiles independent of intrinsic thyroid pathology, often resulting in low T3 levels with normal or low TSH.

Clinical Implications and Management Pathways

Abnormal thyroid function test results require a structured approach based on the severity and type of dysfunction. Mild deviations may warrant observation and lifestyle modifications, whereas significant abnormalities necessitate pharmacological intervention or further diagnostic imaging. For hyperthyroidism, the choice of treatment—antithyroid medications, radioactive iodine therapy, or surgery—depends on the underlying cause and patient-specific factors. In hypothyroidism, hormone replacement therapy is typically required, with careful titration to optimize TSH levels. Given these nuances, a stratified approach is essential to guide evaluation and therapeutic intervention:

- Advanced Diagnostics: Additional imaging modalities, such as thyroid ultrasonography, radioactive iodine uptake studies, and fine-needle aspiration biopsy, may be employed for etiological delineation.

- Pharmacotherapy: Levothyroxine remains the gold standard treatment for hypothyroidism, requiring individualized dose titration based on TSH levels. Antithyroid agents (e.g., methimazole, propylthiouracil), radioiodine therapy, or thyroidectomy may be indicated for hyperthyroidism.

- Nutritional and Lifestyle Considerations: Ensuring adequate intake of iodine, selenium, and vitamin D, coupled with stress modulation strategies and avoidance of goitrogenic foods, is integral to thyroid health.

- Longitudinal Monitoring: Serial thyroid function assessments are essential for evaluating treatment efficacy, detecting disease progression, and adjusting therapeutic strategies.

- Thyroid Cancer Surveillance: In patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma, periodic thyroglobulin measurement, TSH suppression therapy, and imaging studies play a role in long-term disease monitoring.

Conclusion

Thyroid function tests serve as indispensable tools in both clinical and research settings, enabling precise assessment of thyroid homeostasis and pathology. A sophisticated understanding of these biomarkers facilitates tailored therapeutic strategies, optimizing patient outcomes in both primary and specialized care settings. With the ongoing advancements in thyroid diagnostics, the integration of molecular testing and next-generation sequencing holds promise for refining thyroid disorder classifications and personalizing treatment paradigms. Specific techniques, such as targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) panels for thyroid cancer mutations (e.g., BRAF, RAS, RET/PTC rearrangements) and gene expression classifiers (e.g., Afirma, ThyroSeq), have enhanced diagnostic precision and risk stratification. These methodologies contribute to more accurate differentiation of benign and malignant thyroid nodules, reducing unnecessary surgical interventions while enabling tailored therapeutic strategies. Further research is warranted to elucidate the intricate mechanisms governing thyroid hormone regulation and its systemic implications across diverse populations.