Significance of Hepatic Enzymes in Blood Biochemistry

The liver serves as a central metabolic hub, playing a crucial role in various physiological processes. These include xenobiotic detoxification, macronutrient metabolism, bile production, and endogenous protein synthesis, all of which are essential for maintaining systemic homeostasis. As a highly dynamic organ, its functional integrity is frequently assessed through biochemical markers, among which hepatic enzymes play a pivotal role. The quantification of these enzymes in serum provides essential diagnostic and prognostic insights into hepatocellular injury, cholestasis, and systemic metabolic dysfunction. This article delineates the biochemical roles of key hepatic enzymes, their clinical relevance, and the implications of aberrant serum levels in pathological conditions, while also examining contemporary diagnostic methodologies and potential therapeutic avenues for liver-related disorders.

Principal Hepatic Enzymes and Their Biochemical Roles

The assessment of hepatic enzymes is a cornerstone of liver function testing (LFT), with specific biomarkers serving as indicators of distinct hepatic processes. These enzymes are integral to hepatocellular function, and their serum levels can provide insight into hepatobiliary integrity, metabolic disorders, and systemic inflammatory states.

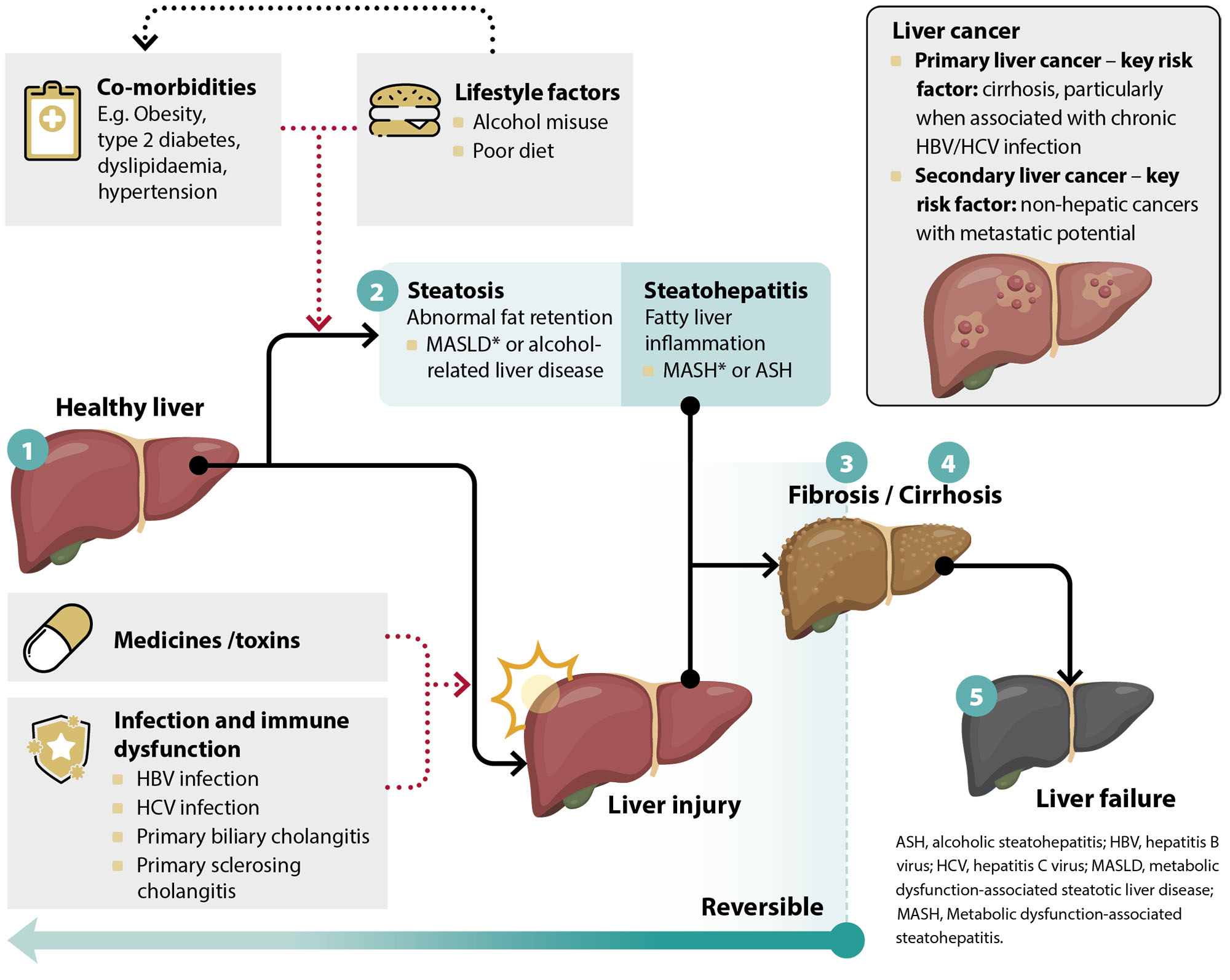

Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT): This aminotransferase, predominantly localized within hepatocytes, catalyzes the transamination of alanine to pyruvate, a critical reaction in gluconeogenesis. Its serum elevation serves as a highly specific marker of hepatocellular injury, frequently observed in conditions such as viral hepatitis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), autoimmune hepatitis, and toxin-induced hepatotoxicity. Persistent ALT elevation is a key indicator for progressive hepatic fibrosis and steatohepatitis.

Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST): Though AST is expressed in hepatocytes, it is also abundant in extrahepatic tissues including the myocardium and skeletal muscle. Consequently, an isolated AST elevation lacks liver specificity. However, an AST/ALT ratio greater than 2:1 is frequently indicative of alcoholic liver disease due to mitochondrial injury. In conditions such as cirrhosis and ischemic hepatitis, AST elevation is often more pronounced than ALT due to widespread hepatocellular necrosis.

Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP): This hydrolase enzyme, primarily associated with hepatobiliary and osseous tissues, plays a role in dephosphorylation reactions. Elevated serum ALP is a hallmark of cholestatic liver disorders, including primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), and bile duct obstruction. ALP levels can also rise in the context of malignancies affecting hepatic or biliary structures and in metabolic bone diseases such as osteomalacia and Paget’s disease.

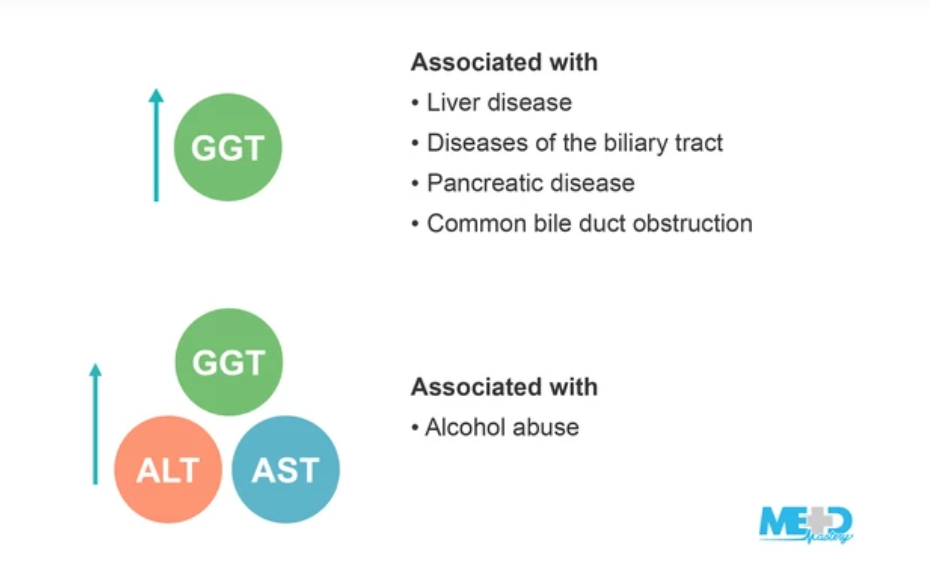

Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase (GGT): Functioning in glutathione metabolism, GGT is highly sensitive to hepatobiliary dysfunction and oxidative stress. Marked elevations often indicate chronic alcohol consumption, hepatotoxic drug exposure, or bile duct pathology. GGT levels are frequently used in conjunction with ALP to differentiate hepatic from non-hepatic causes of enzyme elevations.

Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH): Although a ubiquitous enzyme catalyzing the interconversion of lactate and pyruvate, LDH elevation in hepatic pathophysiology is non-specific. Elevated LDH is often observed in ischemic liver injury, systemic hemolysis, and malignancies with hepatic involvement, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and metastatic liver disease.

Clinical Utility of Hepatic Enzyme Analysis

Hepatic enzyme profiling provides critical diagnostic and prognostic value in hepatology and general internal medicine. Key applications include:

- Hepatic Pathology Diagnosis: Abnormal enzyme profiles facilitate the identification of conditions such as viral hepatitis, cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and metabolic liver disorders such as Wilson’s disease and hemochromatosis.

- Monitoring Disease Progression: Chronic liver diseases necessitate serial enzyme evaluations to assess fibrosis progression, response to antiviral therapy, and effectiveness of lifestyle interventions.

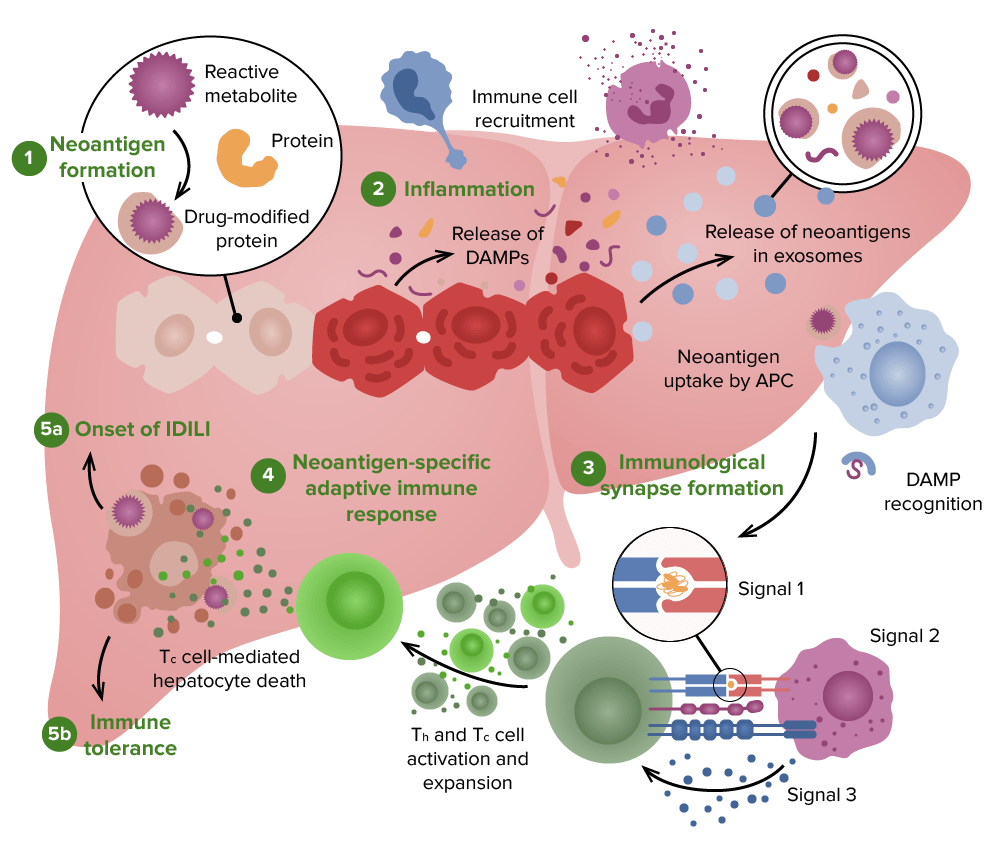

- Evaluating Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI): Many pharmacologic agents, including statins, antiepileptics, and immunosuppressants, can induce hepatocellular or cholestatic injury, warranting routine biochemical monitoring. Emerging biomarkers such as microRNAs and bile acid profiles are being explored to enhance early detection of DILI. MicroRNAs have shown promise in distinguishing between different types of liver injury and may serve as early indicators of hepatocellular stress before overt enzyme elevations occur. Similarly, bile acid profiles offer insights into hepatic metabolic function and cholestasis, providing a potential non-invasive method for assessing liver injury severity. While these biomarkers are still under investigation, ongoing clinical trials and multi-cohort studies aim to validate their utility in routine hepatology practice.

- Differentiating Hepatic vs. Extrahepatic Disorders: AST/ALT ratios, in conjunction with ALP and GGT levels, aid in distinguishing hepatocellular damage from cholestatic or infiltrative liver diseases.

Interpreting Liver Enzyme Aberrations

Serum enzyme deviations from physiological reference ranges necessitate a contextualized interpretation considering clinical presentation, comorbid conditions, and imaging findings. Factors such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, medication use, alcohol consumption, and recent strenuous physical activity can influence enzyme levels independently of primary liver pathology. Additionally, extrahepatic conditions such as myocardial infarction, hemolysis, or muscle disorders may contribute to abnormal readings, necessitating a comprehensive differential diagnosis to avoid misinterpretation.

- Mild Elevation (1-2× Upper Limit of Normal [ULN]): Frequently associated with transient hepatic stressors such as viral infections, mild hepatic steatosis, or non-hepatotoxic medication use. Lifestyle modification and close monitoring are often recommended.

- Moderate Elevation (2-5× ULN): Suggestive of significant hepatic insult, including acute viral hepatitis, alcoholic hepatitis, or hepatotoxicity secondary to pharmacological agents. Further evaluation via liver elastography or biopsy may be warranted.

- Severe Elevation (>5× ULN): Indicative of severe hepatocellular necrosis, as seen in fulminant hepatitis, acute liver failure, or ischemic liver injury. Urgent intervention, including hospitalization and possible liver transplantation evaluation, may be necessary.

Strategies for Maintaining Hepatic Homeostasis

Given the liver’s regenerative potential and critical metabolic role, maintaining hepatic health necessitates proactive interventions:

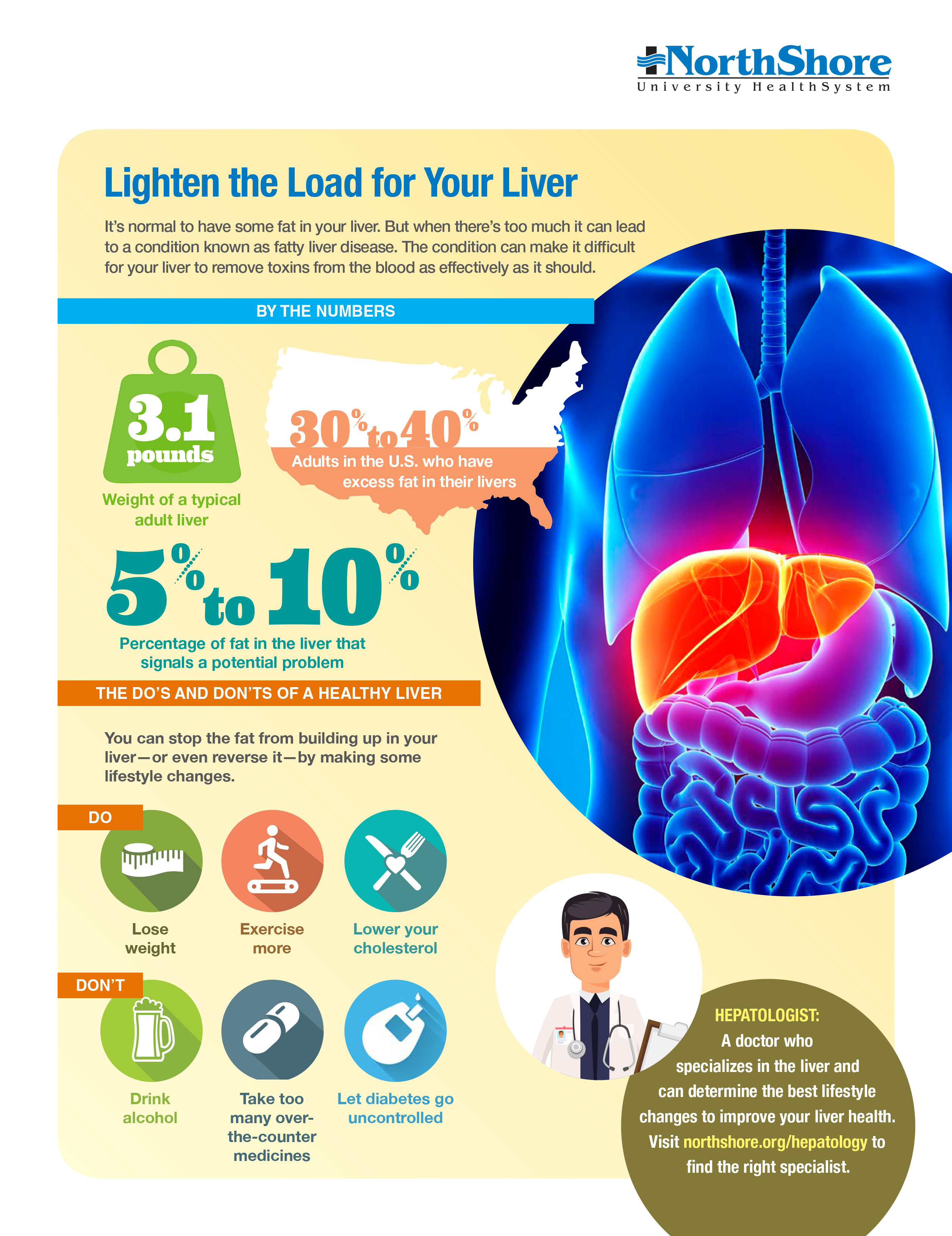

- Nutritional Optimization: Diets enriched in antioxidants, polyphenols, and hepatoprotective nutrients such as omega-3 fatty acids mitigate hepatic oxidative stress and steatosis. Specific dietary components such as turmeric (curcumin), green tea (catechins), and coffee have demonstrated hepatoprotective effects by modulating inflammatory pathways and oxidative stress. Additionally, adherence to a Mediterranean diet, which emphasizes olive oil, nuts, fish, and whole grains, has been associated with reduced hepatic fat accumulation and improved liver enzyme profiles. Emerging evidence suggests that Mediterranean and plant-based diets confer hepatoprotective benefits.

- Alcohol Moderation: Chronic ethanol exposure potentiates hepatic fibrosis via oxidative injury and inflammation, necessitating stringent consumption control. Recent studies highlight the role of abstinence in reversing early-stage liver fibrosis.

- Physical Activity Enhancement: Regular exercise modulates lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity, reducing hepatic fat accumulation in NAFLD. Resistance training, in particular, has shown promising effects in reducing hepatic fat content.

- Minimizing Hepatotoxin Exposure: Judicious use of hepatotoxic medications, coupled with avoidance of environmental toxins, is critical for preserving hepatic function. Occupational exposure to hepatotoxic agents such as aflatoxins and industrial solvents should be monitored.

- Metabolic Syndrome Management: Dysregulated glucose and lipid metabolism exacerbate hepatic steatosis and fibrosis, warranting comprehensive metabolic risk mitigation. Pharmacologic interventions such as GLP-1 receptor agonists are increasingly being studied for their hepatoprotective effects in NAFLD.

Conclusion

The measurement of hepatic enzymes is indispensable in hepatobiliary diagnostics, offering insights into hepatocellular integrity, bile flow dynamics, and systemic metabolic perturbations. A nuanced interpretation of ALT, AST, ALP, GGT, and LDH profiles facilitates precise disease characterization and therapeutic decision-making. With advancements in non-invasive biomarkers, imaging modalities, and targeted therapeutics, the landscape of hepatology continues to evolve, underscoring the need for ongoing research and clinical vigilance in liver disease management. Notably, the development of liquid biopsy techniques utilizing circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and extracellular vesicles has shown promise for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Additionally, novel antifibrotic agents targeting hepatic stellate cell activation and inflammation, such as FGF19 analogs and FXR agonists, are being actively investigated as potential therapeutic strategies for progressive liver diseases.