Inflammatory Markers in Blood Tests:

CRP, ESR, and Related Insights

The assessment of systemic inflammation through laboratory biomarkers is an essential component of clinical and research-based medical diagnostics. Among the most frequently utilized markers,C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) serve as crucial indicators in the identification, monitoring, and prognostication of inflammatory and immune-mediated disorders. This discourse aims to delineate the mechanistic underpinnings, clinical applicability, and interpretative nuances of these inflammatory markers within contemporary medical practice. Additionally, the role of novel inflammatory biomarkers, their integration into precision medicine, and their implications for disease stratification and therapeutic intervention will be explored.

C-Reactive Protein (CRP): A Precision Biomarker of Acute Inflammation

CRP, a hepatically synthesized acute-phase reactant, exhibits a rapid kinetic profile, with levels rising within hours in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6). Its elevation signifies an acute inflammatory state, rendering it highly sensitive for early disease detection and progression monitoring. The clinical utility of CRP extends beyond mere inflammatory assessment, with growing applications in risk stratification, prognosis evaluation, and therapeutic monitoring.

Clinical Significance of CRP

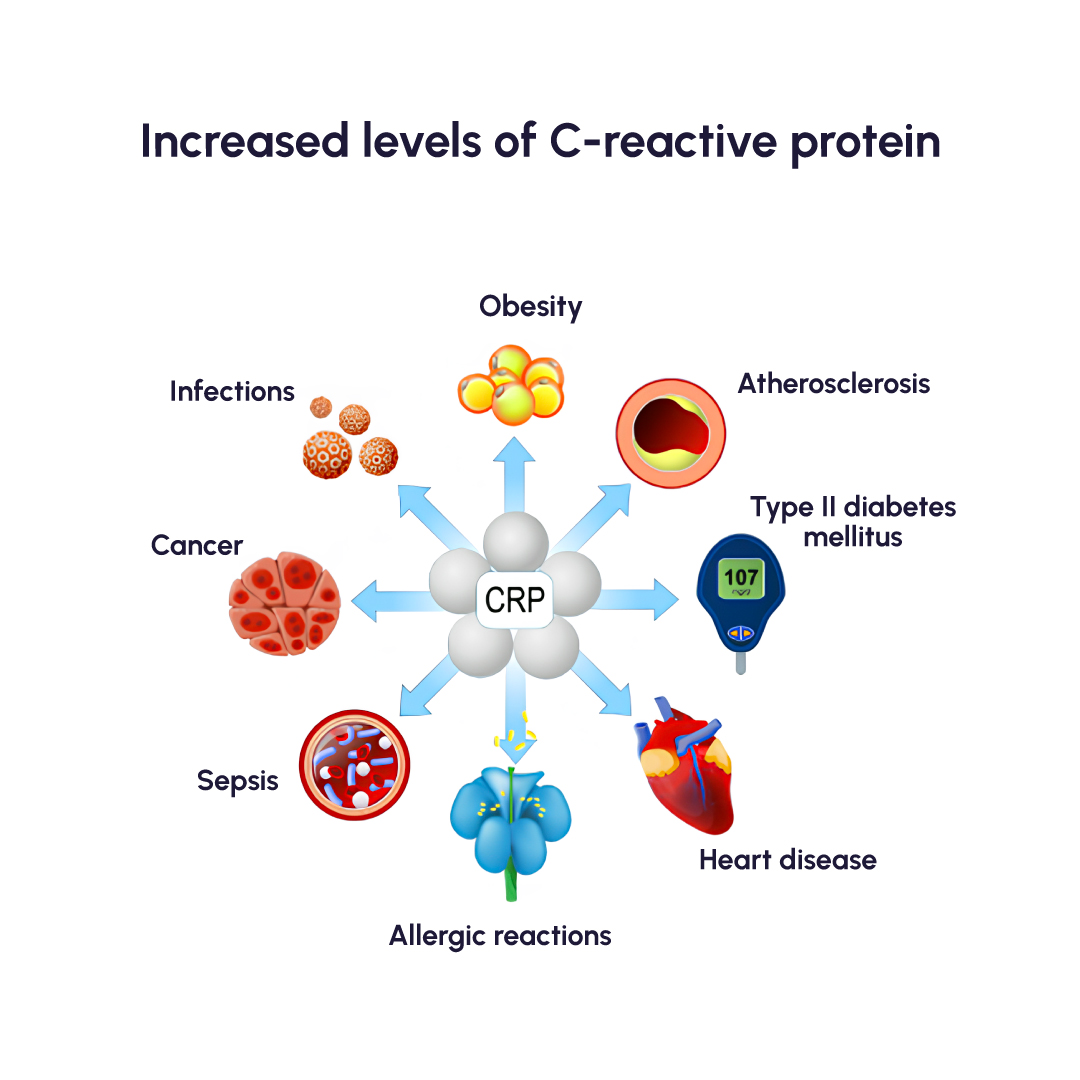

- Infectious Pathologies: Markedly increased CRP levels are observed in bacterial infections, pneumonia, and septic states, correlating with disease severity.

- Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases: Chronic inflammatory conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), are often accompanied by persistently elevated CRP levels.

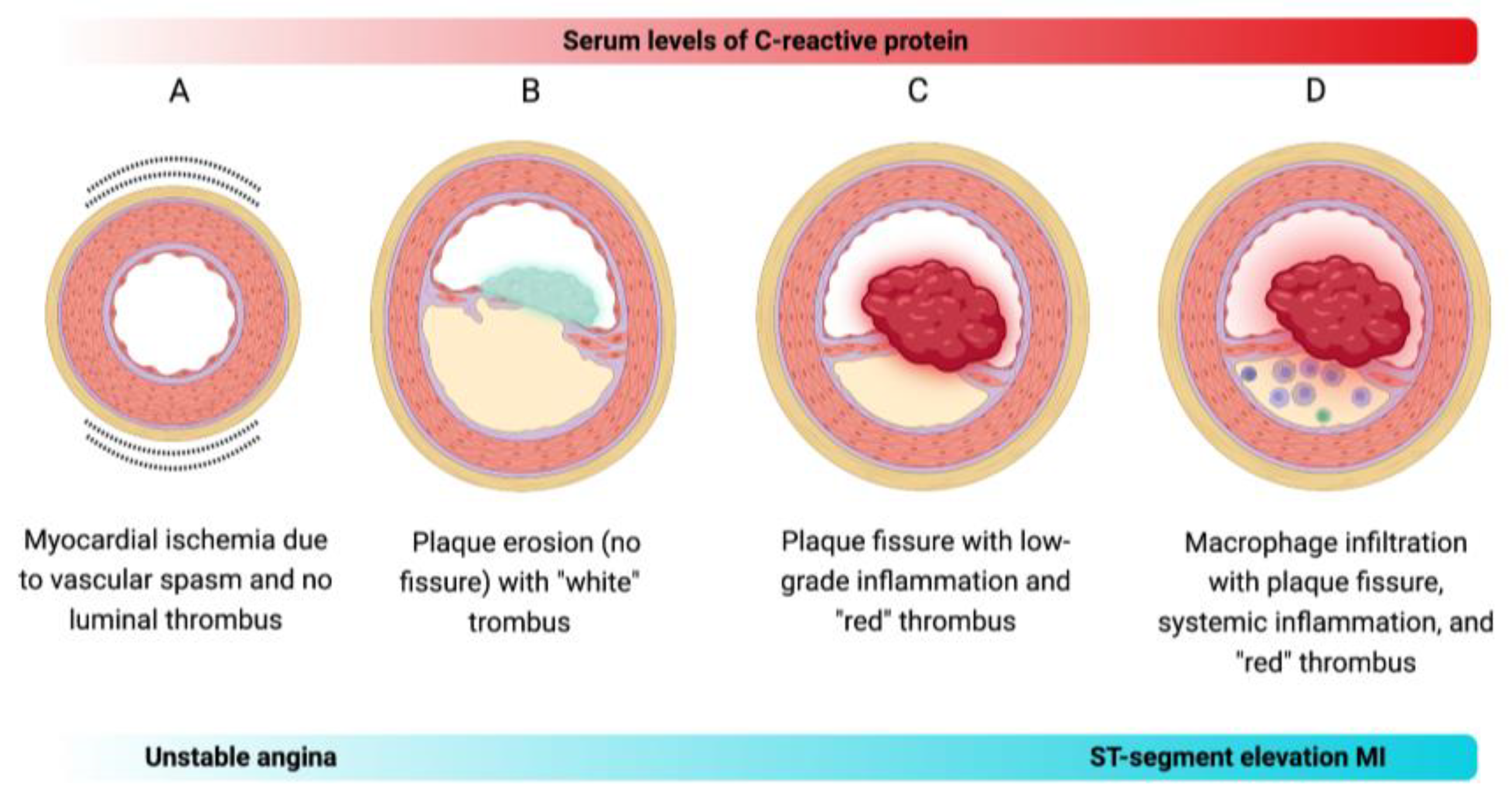

- Cardiovascular Risk Stratification: High-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) is an established biomarker for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk, with implications for both primary and secondary prevention strategies.

- Postoperative and Trauma-Associated Inflammation: CRP is instrumental in the early detection of post-surgical infections and inflammatory sequelae following major surgical interventions.

- Oncologic Implications: Elevated CRP has been correlated with tumor progression, metastasis, and overall prognosis in malignancies such as colorectal, lung, and pancreatic cancers.

Interpreting CRP Levels

- Physiological Baseline: <1 mg/L (indicating minimal systemic inflammation)

- Mildly Elevated: 1-10 mg/L (suggestive of low-grade inflammation, viral infections, or chronic inflammatory states)

- Moderate to High Elevation: >10 mg/L (indicative of significant inflammation, bacterial infections, or tissue injury)

- Severe Elevation: >100 mg/L (highly suggestive of systemic bacterial infections, sepsis, or major inflammatory conditions)

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR):

A Chronic Inflammation Indicator

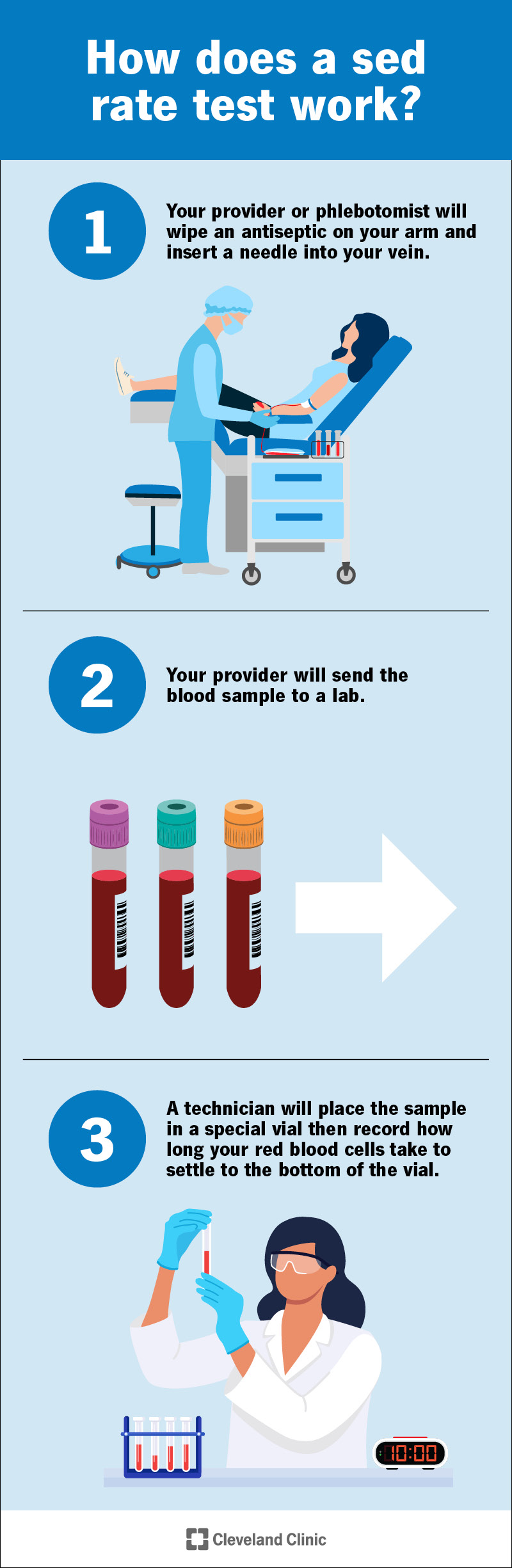

ESR, a nonspecific marker of inflammation, quantifies the rate at which erythrocytes sediment in plasma over time. Its elevation often reflects prolonged inflammatory states and is influenced by plasma protein alterations, particularly fibrinogen. Despite its historical significance, the specificity of ESR remains limited, necessitating its use in conjunction with other biomarkers for robust diagnostic precision.

Clinical Significance of ESR

- Chronic Inflammatory and Autoimmune Disorders: Elevated ESR is commonly observed in polymyalgia rheumatica, SLE, and rheumatoid arthritis, serving as an adjunctive diagnostic and monitoring tool.

- Infectious Diseases: Persistently high ESR levels can indicate chronic infections, including tuberculosis, subacute bacterial endocarditis, and osteomyelitis.

- Oncologic Correlations: Certain malignancies, particularly multiple myeloma and lymphoproliferative disorders, exhibit significantly elevated ESR due to increased circulating immunoglobulins and cytokine-mediated inflammatory responses.

- Tissue Injury and Post-Surgical Recovery: ESR trends can provide insights into the resolution of inflammation following trauma or surgical intervention.

Interpreting ESR Levels

- Physiological Range:

- Men: 0-15 mm/hr

- Women: 0-20 mm/hr

- Mild Elevation: 20-40 mm/hr (suggestive of mild inflammatory activity or low-grade infections)

- Moderate Elevation: 40-70 mm/hr (correlates with significant inflammatory burden)

- Marked Elevation: >70 mm/hr (highly indicative of severe infection, systemic autoimmune disease, or malignancy)

CRP vs. ESR:

Comparative Utility in Clinical Practice

Although both CRP and ESR serve as markers of inflammation, their distinct physiological characteristics underpin their differential clinical applications:

- Temporal Kinetics: CRP exhibits a rapid rise and decline, whereas ESR demonstrates a more prolonged response to inflammation.

- Specificity and Sensitivity: CRP is a more sensitive and specific indicator of acute inflammation, particularly in bacterial infections, while ESR is more reflective of chronic inflammatory conditions.

- Confounding Variables: CRP levels are not significantly affected by hematologic conditions, whereas ESR can be altered by anemia, polycythemia, and plasma protein abnormalities.

- Prognostic Value: CRP, particularly hs-CRP, has emerging prognostic implications in cardiovascular diseases and malignancies, whereas ESR remains a secondary marker in disease monitoring.

Emerging Inflammatory Biomarkers and Future Directions

Beyond CRP and ESR, additional biomarkers have gained traction in the assessment of inflammatory states:

- Procalcitonin (PCT): A highly specific biomarker for distinguishing bacterial from viral infections, particularly in sepsis and lower respiratory tract infections.

- Ferritin: Elevated in chronic inflammation, malignancies, and conditions such as hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH).

- Cytokine Profiles (IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α): Increasingly utilized in research and specialized clinical settings to delineate inflammatory pathophysiology.

- Fibrinogen: A coagulation cascade protein with dual roles in hemostasis and systemic inflammation.

- Calprotectin: Emerging as a valuable biomarker in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), with potential implications for therapeutic monitoring.

- Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR): A systemic inflammatory index gaining attention in oncologic and cardiovascular risk assessment.

Conclusion

Inflammatory biomarkers such as CRP and ESR are indispensable tools in the diagnostic and prognostic landscape of inflammatory, infectious, and autoimmune diseases. While CRP serves as a rapid and specific marker of acute inflammation, ESR provides insight into chronic inflammatory states. Their integration into clinical practice necessitates a sophisticated understanding of their biological underpinnings, interpretation within disease-specific contexts, and correlation with adjunctive laboratory and imaging modalities. Moreover, the evolving role of novel inflammatory biomarkers, including cytokine profiling, ferritin, and PCT, signifies a paradigm shift toward precision medicine. Future advancements in biomarker research hold promise for refining diagnostic accuracy, enhancing disease stratification, and ultimately personalizing therapeutic strategies to optimize patient outcomes.