Hemoglobin and Ferritin: Critical Biomarkers in Hematological Homeostasis and Anemia Pathophysiology

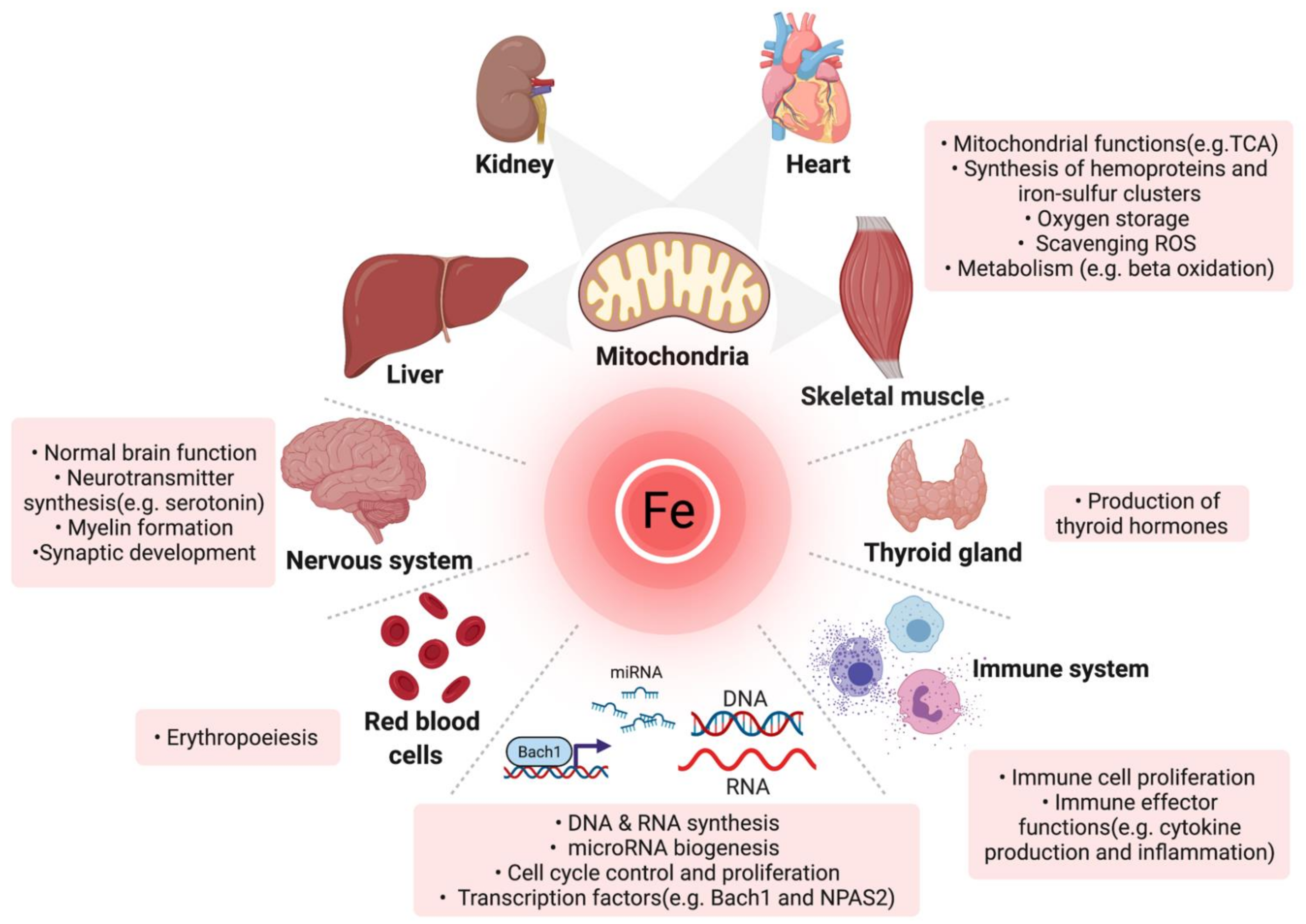

Hemoglobin and ferritin serve as pivotal biomarkers in hematology, offering profound insights into oxygen transport efficacy and iron metabolism. Their assessment is integral to the diagnosis and management of anemia, iron dysregulation, and broader hematopoietic disorders. A nuanced understanding of their biochemical properties, physiological thresholds, and pathophysiological deviations is essential for clinicians and researchers engaged in hematological studies. Further investigation into their regulatory mechanisms, including the role of hepcidin-ferroportin interactions in iron homeostasis and the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway in erythropoiesis, continues to shape advanced diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in modern medicine. Additionally, the crosstalk between inflammatory cytokines and erythropoietic signaling pathways highlights the complex interplay between systemic metabolism and hematopoiesis.

Hemoglobin: The Oxygen-Binding Metalloprotein

Biochemical Structure and Functional Significance

Hemoglobin is a tetrameric metalloprotein residing in erythrocytes, composed of two α and two β globin chains, each harboring a heme moiety. The heme iron reversibly binds molecular oxygen, facilitating systemic oxygenation and carbon dioxide transport. Its structural integrity and functional dynamics are critical for maintaining optimal tissue oxygenation and metabolic homeostasis. Any genetic or acquired alterations in hemoglobin synthesis or function can have profound hematological and systemic repercussions. Notable genetic mutations include β-thalassemia (HBB gene mutations), sickle cell disease (HbS mutation), and hereditary spherocytosis (ANK1, SPTB, or SPTA1 mutations). Acquired conditions such as lead poisoning, chronic kidney disease, and myelodysplastic syndromes can also disrupt hemoglobin function and erythropoiesis, leading to anemia and systemic complications.

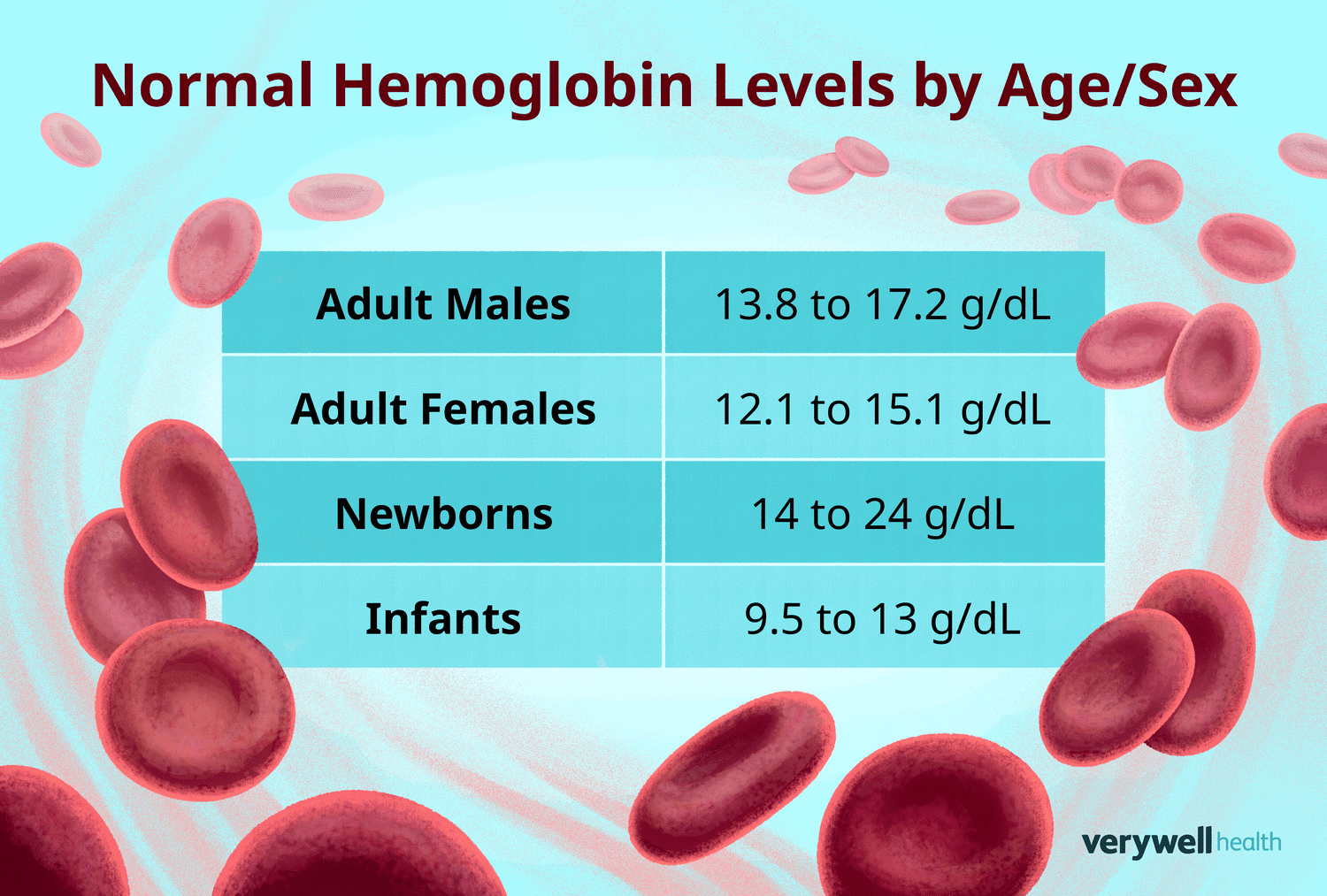

Physiological Reference Ranges and Hematopoietic Regulation

Hemoglobin concentrations are subject to variation based on demographic and physiological parameters:

- Men: 13.8–17.2 g/dL

- Women: 12.1–15.1 g/dL

- Children: 11–16 g/dL

- Pregnant Women: 11–14 g/dL

Erythropoiesis is regulated by erythropoietin (EPO), a glycoprotein hormone synthesized in the renal peritubular cells. Hypoxic conditions stimulate EPO production, thereby enhancing hemoglobin synthesis. Dysregulation in erythropoiesis, as seen in chronic kidney disease, malignancies, or myelodysplastic syndromes, directly influences hemoglobin levels and necessitates targeted therapeutic interventions.

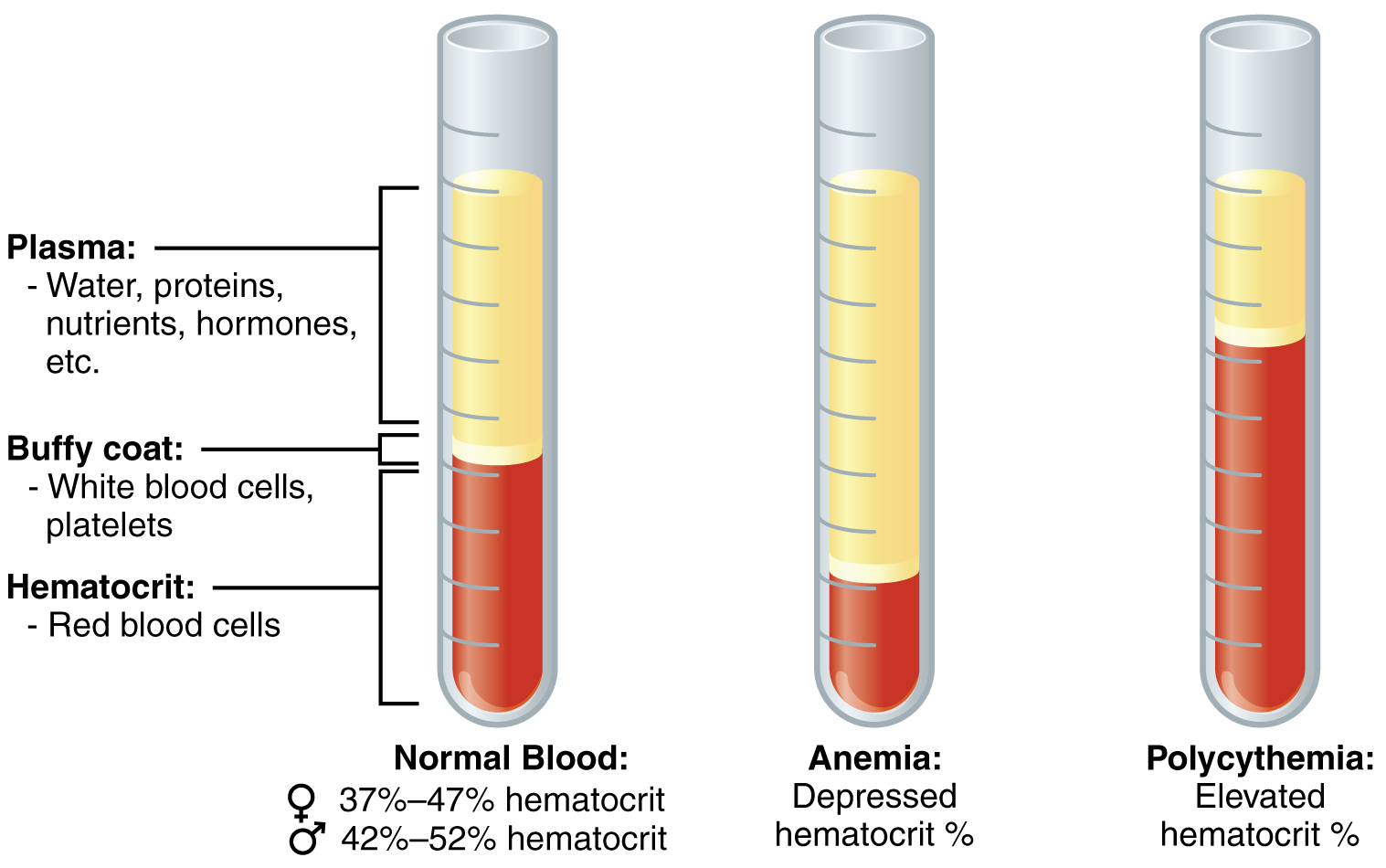

Hypohemoglobinemia:

Etiological Considerations and Clinical Manifestations

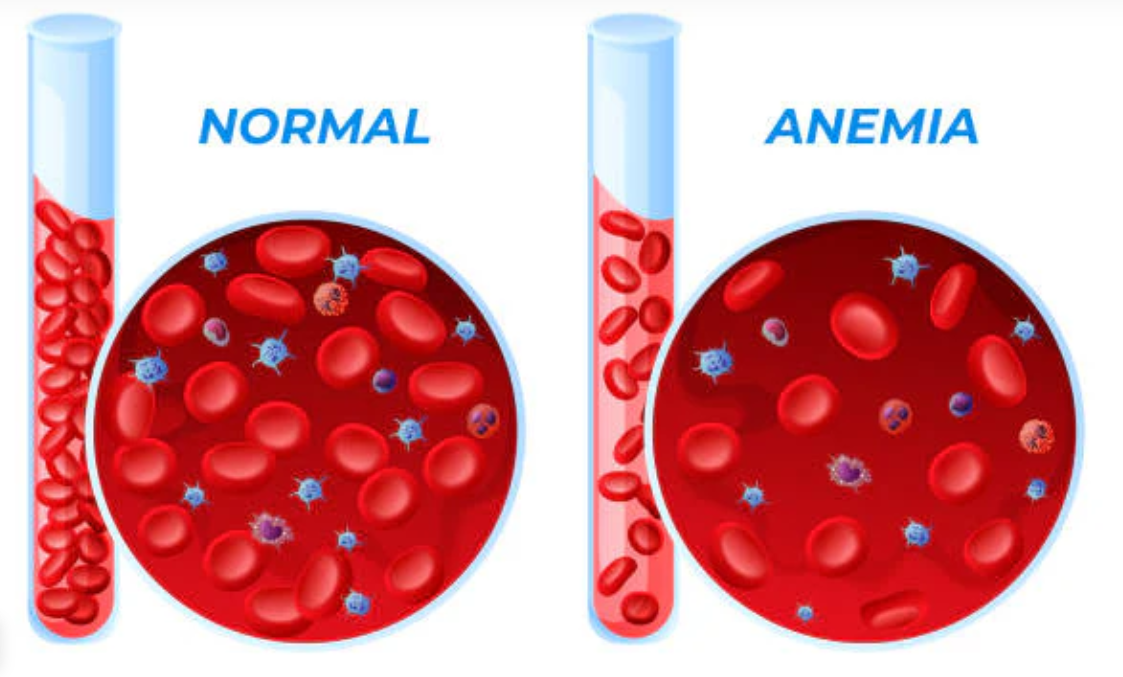

Suboptimal hemoglobin levels are indicative of anemic syndromes, which may arise from diverse etiologies:

- Iron-deficiency anemia (IDA): Resulting from chronic hemorrhage, malabsorption syndromes, or insufficient dietary intake.

- Megaloblastic anemia: Due to vitamin B12 or folate insufficiency, leading to defective DNA synthesis.

- Anemia of chronic disease (ACD): Secondary to inflammatory cytokine-mediated iron sequestration.

- Hemoglobinopathies: Genetic mutations affecting globin synthesis, including thalassemias and sickle cell disease.

Clinical manifestations include exertional dyspnea, pallor, tachycardia, and cognitive dysfunction, underscoring the necessity for early detection and intervention. Recent research also implicates chronic inflammation and oxidative stress as contributors to hypohemoglobinemia in metabolic syndromes and neurodegenerative conditions.

Polycythemia:

Pathophysiology and Implications

Elevated hemoglobin levels may be secondary to:

- Hypoxic stimuli: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), high-altitude adaptation.

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms: Polycythemia vera, characterized by JAK2 mutations.

- Relative polycythemia: Resulting from hemoconcentration due to dehydration.

Persistent polycythemia predisposes individuals to thromboembolic complications, necessitating therapeutic phlebotomy or cytoreductive therapy. The interplay between erythropoiesis, iron metabolism, and inflammatory markers is an area of ongoing research in hematological malignancies. Recent studies have elucidated the role of hepcidin and ferroportin dysregulation in conditions such as myelodysplastic syndromes and leukemia-associated anemia. Additionally, inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 have been shown to modulate iron homeostasis, further complicating anemia management in cancer patients. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for developing targeted therapeutic strategies, including novel erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and iron modulation therapies.

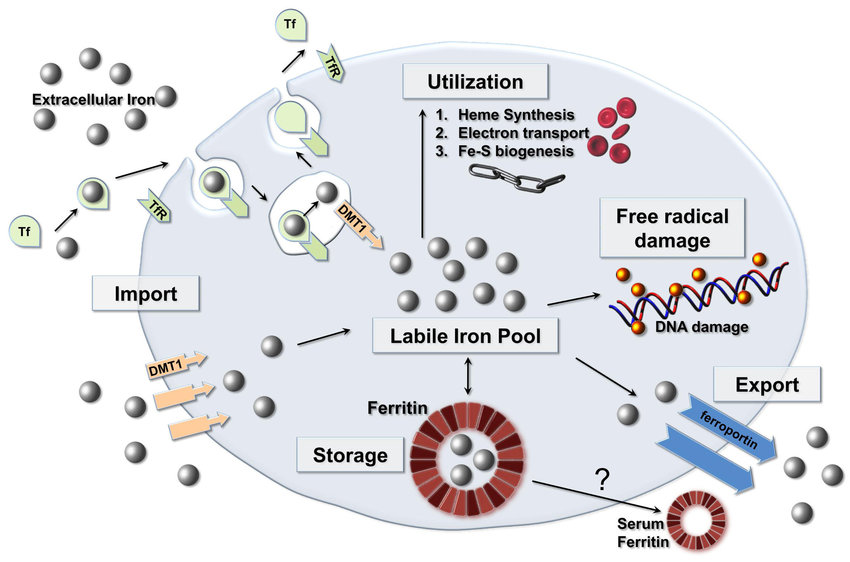

Ferritin: The Intracellular Iron Reservoir

Molecular Function and Iron Homeostasis

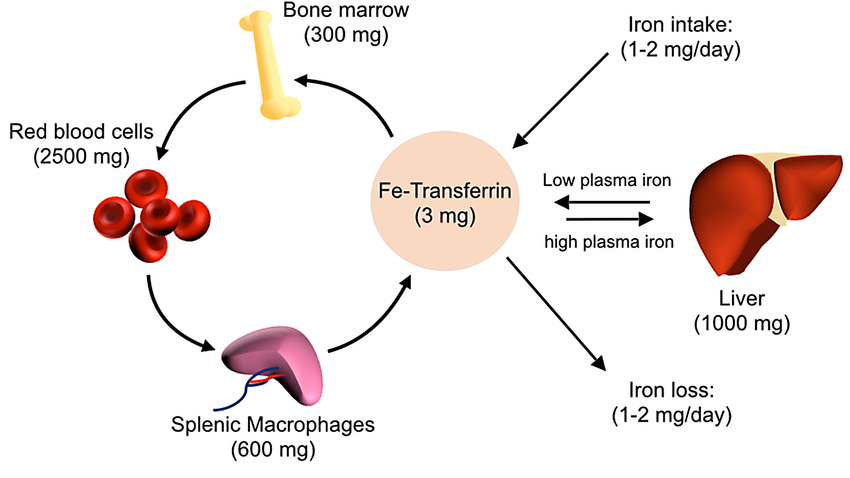

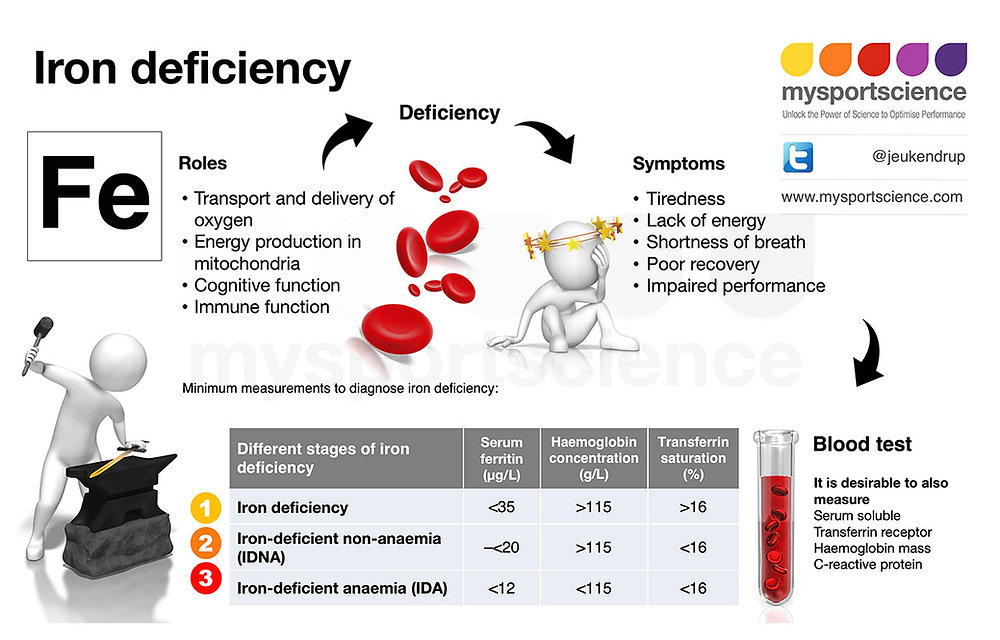

Ferritin is a cytosolic protein complex that sequesters bioavailable iron, mitigating oxidative stress while maintaining systemic iron homeostasis. It exists predominantly in hepatocytes and reticuloendothelial cells, serving as a surrogate marker for total body iron stores. Ferritin levels correlate with inflammatory states, as it functions as an acute-phase reactant, further complicating the interpretation of iron status in clinical practice.

Reference Intervals and Clinical Significance

Ferritin levels vary based on physiological status:

- Men: 24–336 ng/mL

- Women: 11–307 ng/mL

- Children: 7–140 ng/mL

Ferritin assays are particularly valuable in distinguishing absolute iron deficiency from functional iron sequestration in chronic diseases. The development of novel biomarkers such as hepcidin, which regulates iron homeostasis, has refined diagnostic capabilities in differentiating iron dysregulation subtypes.

Hypoferritinemia: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Clinical Repercussions

Diminished ferritin levels reflect depleted iron reserves, a hallmark of IDA. Common causative factors include:

- Inadequate iron intake

- Chronic blood loss (e.g., menorrhagia, gastrointestinal bleeding)

- Impaired absorption (e.g., celiac disease, post-bariatric surgery)

Symptoms such as fatigue, koilonychia, and pica necessitate prompt iron repletion strategies. Emerging research explores the role of ferritin in neurodevelopmental disorders, particularly autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), highlighting its potential impact beyond hematology. Recent studies suggest that ferritin levels may influence neurocognitive development and synaptic plasticity, emphasizing the need for further investigation into iron metabolism in neurological conditions.

Hyperferritinemia:

Etiologies and Clinical Significance

Elevated ferritin concentrations may denote:

- Hemochromatosis: Genetic iron overload disorders due to HFE mutations.

- Chronic inflammatory states: Ferritin acts as an acute-phase reactant in systemic inflammation.

- Malignancies: Elevated levels in hematologic neoplasms such as lymphoma.

Excessive iron deposition engenders oxidative tissue damage, warranting iron chelation therapy when indicated. The study of ferritinopathies, where excess ferritin aggregates in tissues, is an emerging field in neurodegenerative and systemic disorders.

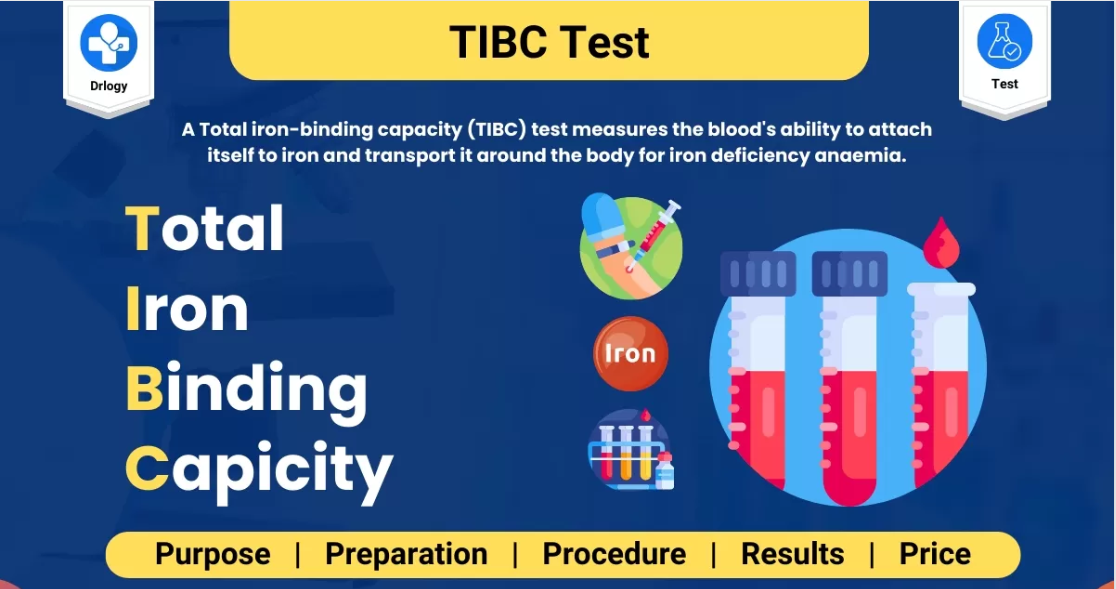

Anemia Diagnosis:

Integrative Hematological Assessments

The diagnostic evaluation of anemia necessitates a multifaceted approach:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Quantification of hemoglobin, hematocrit, and red cell indices.

- Serum Ferritin and Iron Panels: Assessment of iron reserves and mobilization.

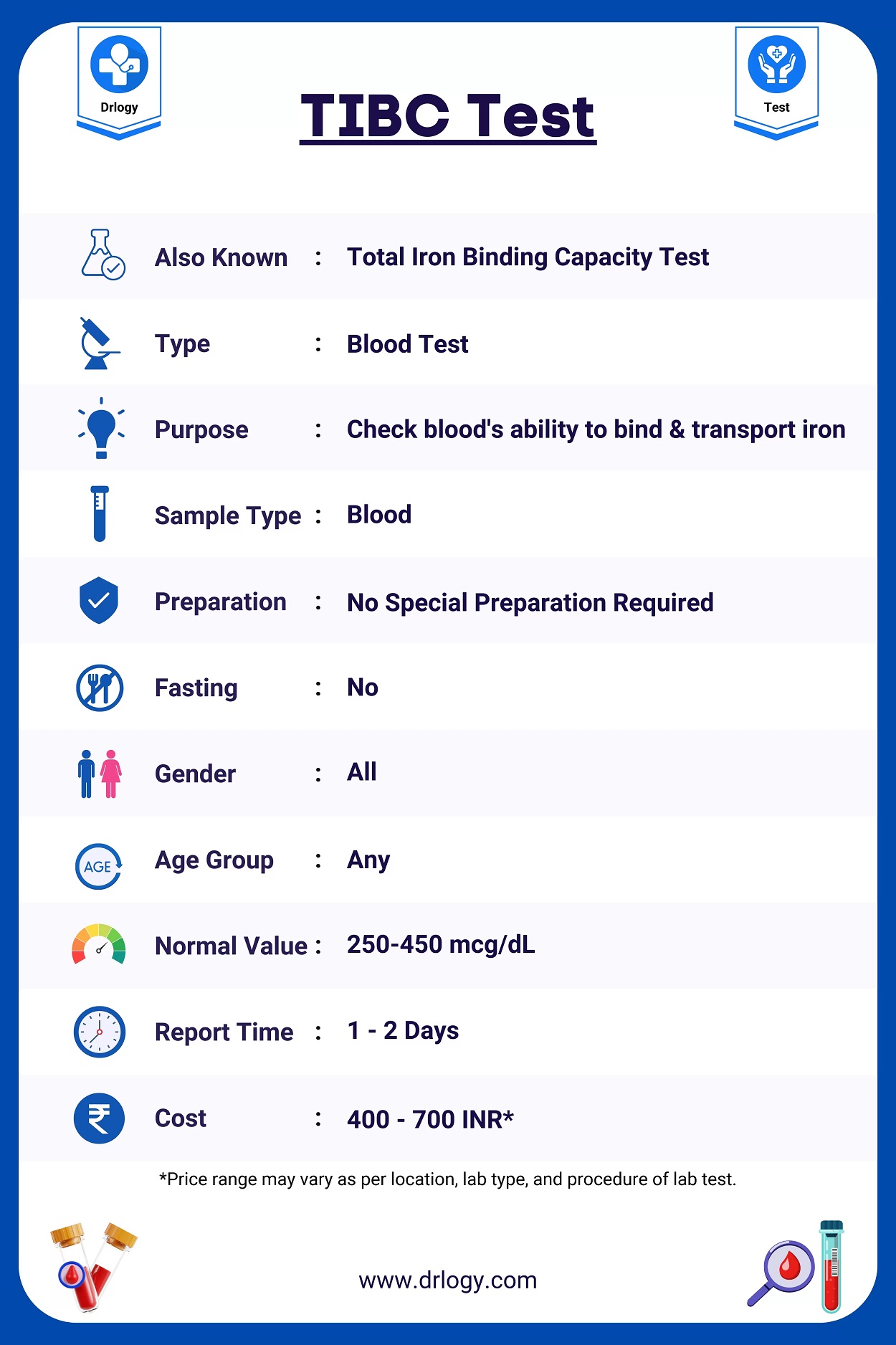

- Total Iron Binding Capacity (TIBC): Evaluation of iron transport capacity.

The concurrence of hypoferritinemia and low hemoglobin is pathognomonic for IDA, whereas normoferritinemia with anemia suggests chronic disease-mediated iron sequestration. Advanced diagnostic tools, including molecular profiling and iron kinetics studies, are expanding the scope of hematological diagnostics.

Therapeutic Interventions and Clinical Management

Management strategies are contingent upon the underlying etiology:

- Iron Deficiency Anemia: Oral ferrous sulfate or intravenous iron formulations.

- Megaloblastic Anemia: B12 or folate supplementation.

- Anemia of Chronic Disease: Targeted management of the primary disorder and judicious use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents.

- Iron Overload Syndromes: Therapeutic phlebotomy and iron chelation to prevent organ dysfunction.

Gene therapy and targeted molecular interventions are emerging as novel approaches in treating hemoglobinopathies and iron dysregulation syndromes.

Conclusion

Hemoglobin and ferritin are indispensable biomarkers in hematological diagnostics, offering critical insights into erythropoiesis and iron metabolism. Their meticulous evaluation facilitates precise diagnosis and tailored therapeutic strategies for anemia and iron dysregulation disorders. Advanced research into molecular hematology continues to refine our understanding of these biomarkers, optimizing patient outcomes through evidence-based interventions. Ongoing studies in the genomic and proteomic landscapes promise novel insights into iron metabolism and erythropoietic regulation, paving the way for next-generation therapeutics in hematology. Recent advancements include the identification of genetic polymorphisms in the TMPRSS6 gene, which influence hepcidin regulation, and the use of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing for correcting mutations in hemoglobinopathies. Additionally, proteomic profiling has enabled the discovery of novel biomarkers for iron overload syndromes and anemia subtypes, improving precision medicine approaches. These innovations hold significant promise for developing targeted therapies that enhance iron homeostasis and erythropoiesis with minimal adverse effects.