Etiology and Pathophysiological Implications of Dysregulated Creatinine and Urea Levels

Introduction

Creatinine and urea serve as pivotal biomarkers for renal function and systemic metabolic homeostasis. Creatinine, a byproduct of phosphocreatine metabolism in skeletal muscle, and urea, the principal nitrogenous waste product derived from hepatic protein catabolism, are both excreted by the kidneys. Deviations from physiological reference ranges may signify underlying pathological processes affecting renal, hepatic, or systemic metabolic pathways. Given their significance in clinical diagnostics, understanding the etiological determinants and clinical ramifications of aberrant creatinine and urea levels is essential. This analysis provides a comprehensive exploration of the mechanisms governing these biomarkers, the conditions that influence their levels, and the systemic repercussions of their dysregulation.

Elevated Creatinine Levels

Etiological Determinants of Hypercreatininemia

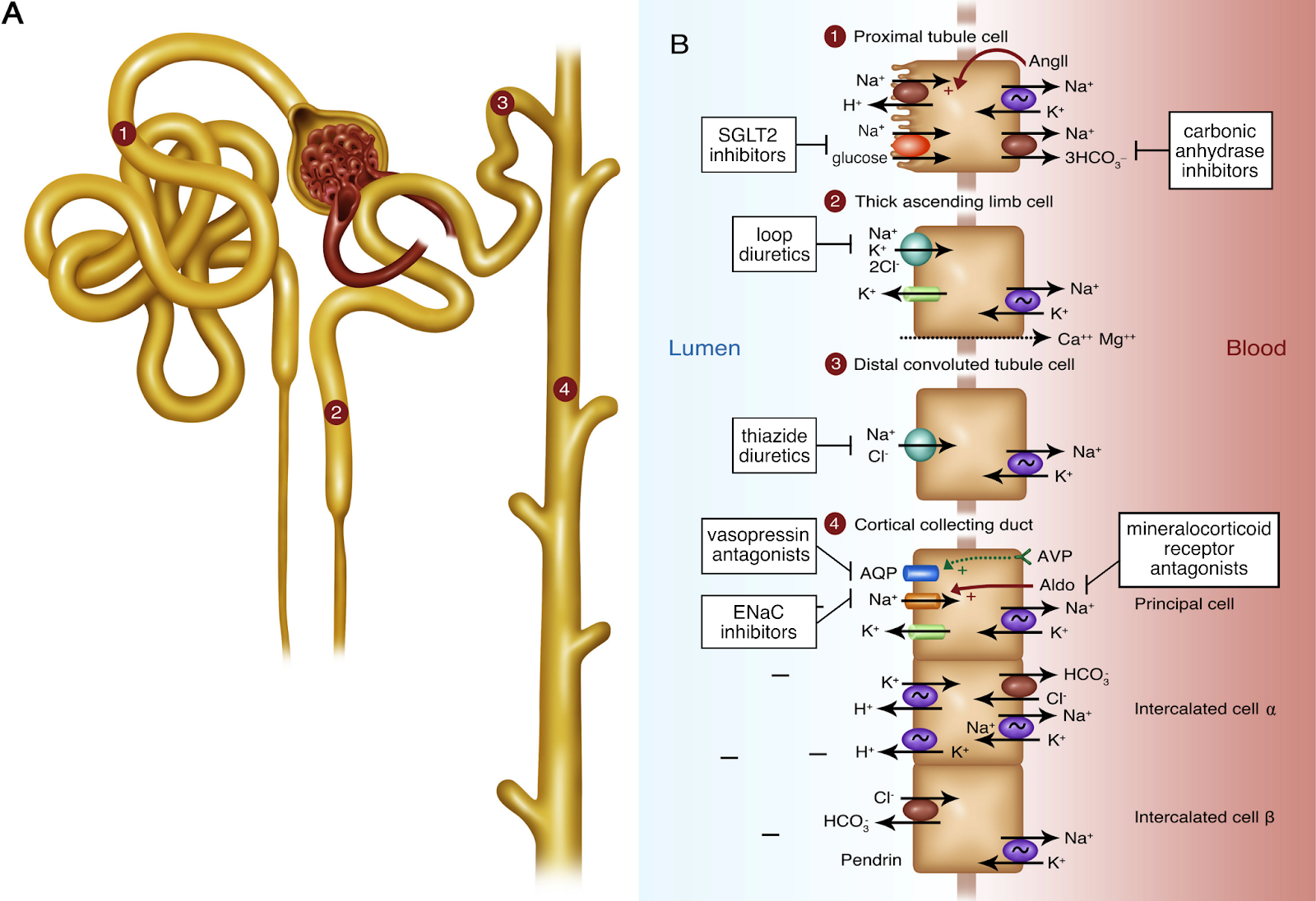

- Renal Insufficiency: Chronic kidney disease (CKD) and acute kidney injury (AKI) impair glomerular filtration, leading to an accumulation of creatinine in the bloodstream. This serves as a key diagnostic indicator of renal dysfunction.

- Hypovolemia and Dehydration: Reduced intravascular volume decreases renal perfusion and glomerular filtration rate (GFR), exacerbating creatinine retention.

- Excessive Protein Intake and Metabolic Demand: Increased dietary protein consumption augments amino acid metabolism, leading to heightened creatinine synthesis.

- Intense Muscular Exertion: Vigorous physical activity induces muscle breakdown, temporarily increasing circulating creatinine levels.

- Pharmacologic Interference: Nephrotoxic agents, such as NSAIDs, ACE inhibitors, and aminoglycosides, alter renal hemodynamics, impairing creatinine clearance.

- Cardiovascular Pathologies: Conditions like congestive heart failure (CHF) and systemic hypoperfusion decrease renal clearance efficiency, resulting in elevated serum creatinine.

- Obstructive Uropathy: Mechanical obstruction due to nephrolithiasis or prostatic hypertrophy impairs urine excretion, leading to secondary renal dysfunction and increased creatinine levels.

Pathophysiological Consequences of Hypercreatininemia

- Electrolyte and Acid-Base Imbalances: Creatinine accumulation often coincides with dysregulated electrolyte homeostasis, predisposing patients to metabolic disturbances.

- Metabolic Acidosis: Impaired hydrogen ion excretion and reduced bicarbonate reabsorption contribute to systemic acidemia, necessitating corrective interventions.

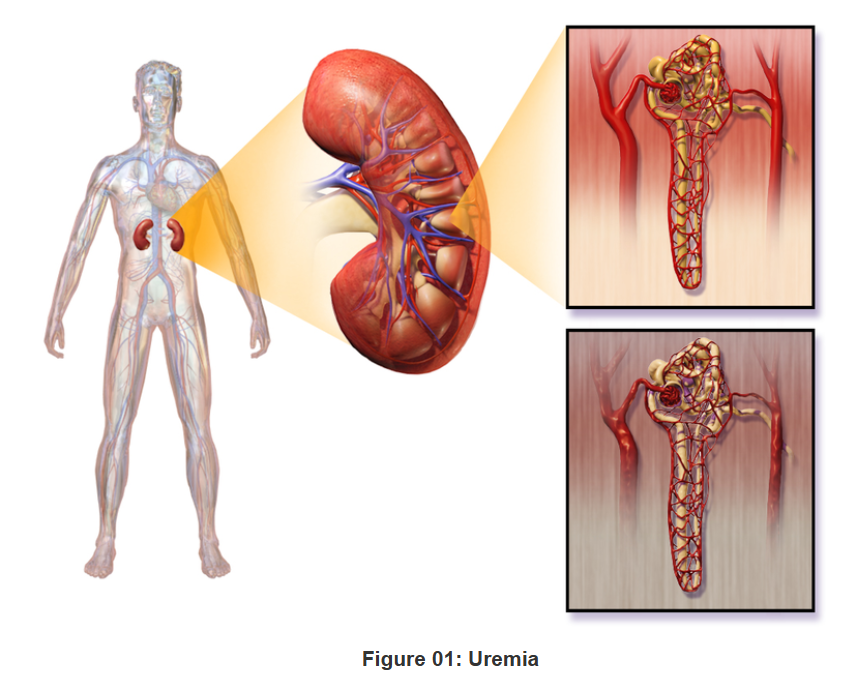

- Uremic Syndrome: Elevated creatinine levels are indicative of systemic uremia, manifesting in cognitive dysfunction, anorexia, and neuromuscular irritability.

- Volume Overload and Hypertension: Renal inefficiency leads to fluid retention, contributing to hypertension and peripheral edema, further exacerbating cardiovascular morbidity.

Diminished Creatinine Levels

Etiological Determinants of Hypocreatininemia

- Sarcopenia and Muscular Atrophy: Age-related muscle loss, neuromuscular disorders, and prolonged immobilization decrease creatinine production, often serving as a marker of frailty in geriatric populations.

- Hepatic Dysfunction: Impaired creatine synthesis due to hepatic insufficiency results in diminished creatinine levels.

- Pregnancy-Associated Hemodilution: Increased plasma volume expansion during gestation leads to dilutional decreases in creatinine concentrations.

- Nutritional Deficiencies: Inadequate dietary protein intake restricts creatinine biosynthesis, which may be indicative of malnutrition.

- Endocrine Dysregulation: Hyperthyroidism and chronic catabolic states accelerate protein turnover, leading to reduced creatinine levels.

Pathophysiological Consequences of Hypocreatininemia

- Muscle Weakness and Functional Impairment: Low creatinine levels may reflect underlying sarcopenia and diminished muscle function.

- Protein-Energy Malnutrition: Prolonged nutritional deficiencies can predispose individuals to immune suppression and impaired wound healing.

- Potential Diagnostic Oversight: Low creatinine levels, if not accurately assessed, may obscure the presence of renal dysfunction, necessitating further evaluation.

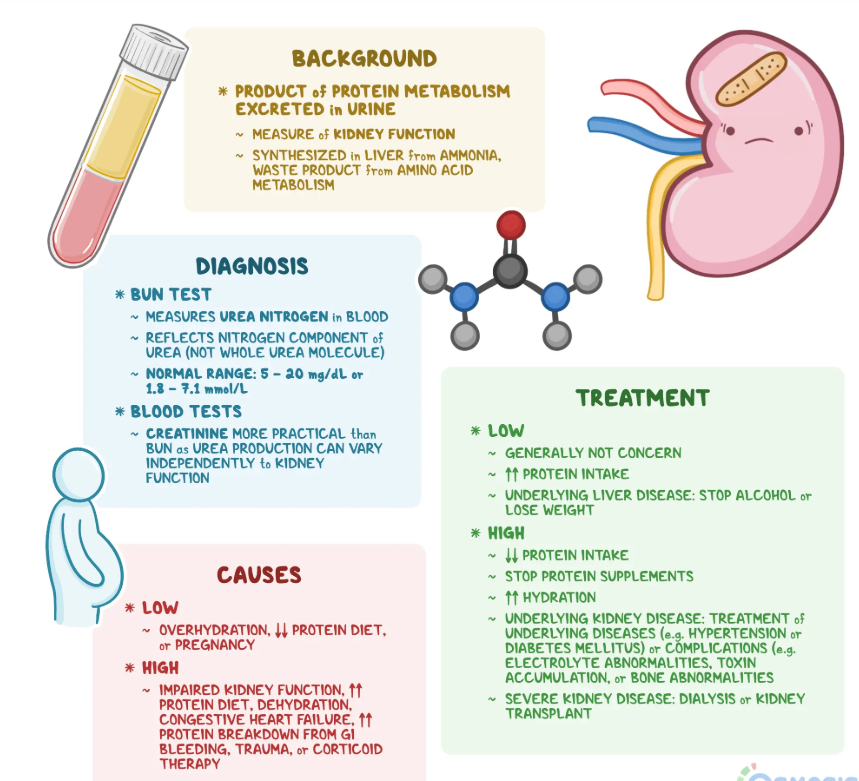

Elevated Urea Levels (Azotemia/Uremia)

Etiological Determinants of Uremia

- Renal Dysfunction: Impaired glomerular filtration in CKD and AKI leads to decreased urea clearance and systemic azotemia.

- Catabolic Hyperactivity: Systemic infections, malignancies, and extensive burns accelerate protein catabolism, increasing urea synthesis.

- Hypovolemia and Dehydration: Reduced circulating volume leads to decreased renal perfusion, impairing urea excretion.

- Hepatorenal Syndrome: Liver failure disrupts urea cycle homeostasis, leading to accumulation of nitrogenous waste.

- Cardiovascular Pathologies: Diminished renal perfusion due to cardiac insufficiency further exacerbates urea retention.

Pathophysiological Consequences of Uremia

- Uremic Encephalopathy: Neurological dysfunction due to excessive uremic toxin accumulation manifests as cognitive impairment, tremors, and altered consciousness.

- Cardiovascular Sequelae: Uremia is associated with accelerated atherosclerosis, increased cardiovascular morbidity, and heightened risk of cardiac events.

- Coagulopathy and Bleeding Diathesis: Platelet dysfunction in severe uremia predisposes to hemorrhagic complications, necessitating hemostatic intervention.

Diminished Urea Levels

Etiological Determinants of Hypouremia

- Hepatic Insufficiency: Dysfunctional hepatic nitrogen metabolism results in reduced urea synthesis.

- Protein-Energy Malnutrition: Chronic protein restriction leads to decreased nitrogenous waste production.

- Overhydration and Dilutional States: Excessive fluid intake causes dilutional hypouremia, potentially masking underlying metabolic imbalances.

- Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders: Anabolic steroid use and inherited urea cycle defects alter nitrogen balance, impacting urea synthesis.

Pathophysiological Consequences of Hypouremia

- Hepatic Dysfunction and Ammonia Accumulation: Reduced urea synthesis may lead to hyperammonemia, manifesting in neurotoxicity and hepatic encephalopathy.

- Fluid Dysregulation and Edema: Impaired osmotic balance due to low urea levels contributes to extracellular volume expansion.

- Maladaptive Nitrogen Balance: Prolonged hypouremia may indicate chronic metabolic insufficiency, with implications for immune function and tissue regeneration.

Conclusion

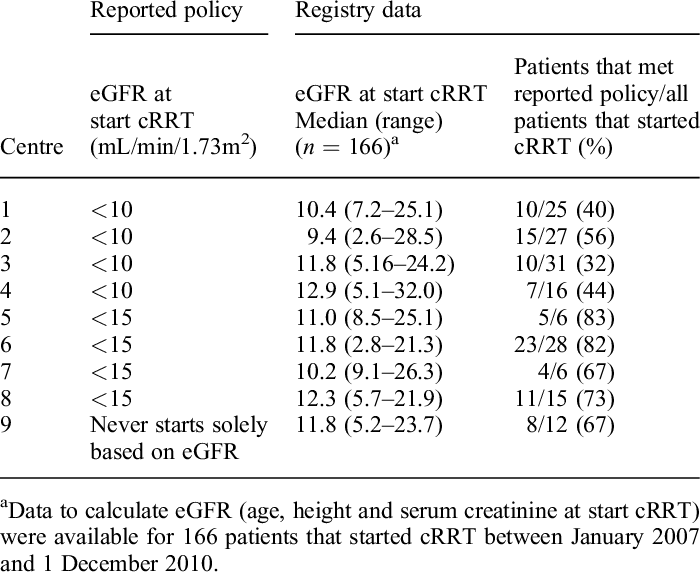

The regulation of creatinine and urea homeostasis is integral to maintaining renal, hepatic, and systemic metabolic equilibrium by ensuring proper nitrogen excretion, acid-base balance, and osmotic stability. These biomarkers also play a crucial role in cardiovascular health, neuromuscular function, and metabolic adaptation to physiological stressors. Hypercreatininemia and hyperuremia are hallmarks of renal insufficiency, while their reductions may signify hepatic dysfunction, malnutrition, or altered metabolic states such as hypermetabolic conditions, endocrine disorders (e.g., Addison’s disease or hyperthyroidism), or chronic inflammatory states. These metabolic disturbances can lead to excessive protein catabolism, altered nitrogen balance, and impaired synthesis of nitrogenous waste products. Understanding the multifaceted etiological and pathophysiological implications of these biomarkers is essential for refining diagnostic precision and therapeutic interventions, particularly in the context of renal replacement therapies, biomarker-driven risk stratification, and individualized treatment regimens. Advances in nephrology and hepatology have underscored the importance of leveraging creatinine and urea kinetics in predictive modeling for disease progression, guiding pharmacological dosing adjustments, and optimizing hemodialysis and continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) protocols. Routine biochemical monitoring, complemented by a comprehensive clinical assessment, remains paramount in mitigating the systemic sequelae associated with nitrogenous waste dysregulation. Standardized protocols such as serial serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) measurements, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) calculations, and 24-hour urine collection for creatinine clearance provide valuable insights into renal function trends. Additionally, emerging technologies, including point-of-care testing and real-time biomarker analysis, enhance early detection and facilitate timely intervention in at-risk populations.